Additive manufactured optical coatings – a realm of new possibilities

An interview about hard coatings and photochromic coatings from the 3D printer

Spectacle lens coatings from the 3D printer – this scenario became reality in fall 2023. An Israeli start-up presented a printer for coating spectacle lenses at the Vision Expo West in Las Vegas. Hard coatings and photochromic coatings can now be applied in optical labs using the additive process. The fact that the developers have decided to revolutionize the ophthalmic market right now is no coincidence, explains Jonathan Jaglom, Chairman and CEO of flō: “I think the traditional ophthalmic industry is hungry for innovation!” In the following interview, the 3D printing expert talks about the possibilities of the new technology, and why additive manufacturing will not just be a flash in the pan in the ophthalmic industry.

3D printing of spectacle lens coatings is a further milestone in the field of additive manufacturing in ophthalmic optics. 3D-printed spectacle frames are already commonplace today, but until now lenses have been a different story.

A few years ago, a company which produced its own spectacle lenses using 3D printing caused a major stir, but at that time the process was not yet suitable for mass production. The company has since been taken over by Meta.

Back then, 3D-printed coatings did not yet exist. This has now changed with the start-up company flō entering the ophthalmic optics market.

With the help of your platform, coatings for spectacle lenses can be applied using additive manufacturing. How did the idea come about to use 3D printing?

Basically, around 80% of our team comes from the field of additive manufacturing. For instance, I was part of the founding team of Stratasys. Today that company is the number one player in the 3D printing industry worldwide with revenue of around $650 million a year. A lot of my knowhow comes from printing, and that is also true for many of my colleagues here at the company. One of them, actually the founder of flō, Dr. Claudio Rottman, is the CTO of the company.

The best way to explain how the idea came about is that it is basically embedded in our mindset. It is a vision. You really develop this sort of mindset. You look at the various ways things are being done around you, and all the time you are questioning whether additive manufacturing could be introduced there.

That means you do not have an “optical background”, so how did the idea of getting into ophthalmic optics come about?

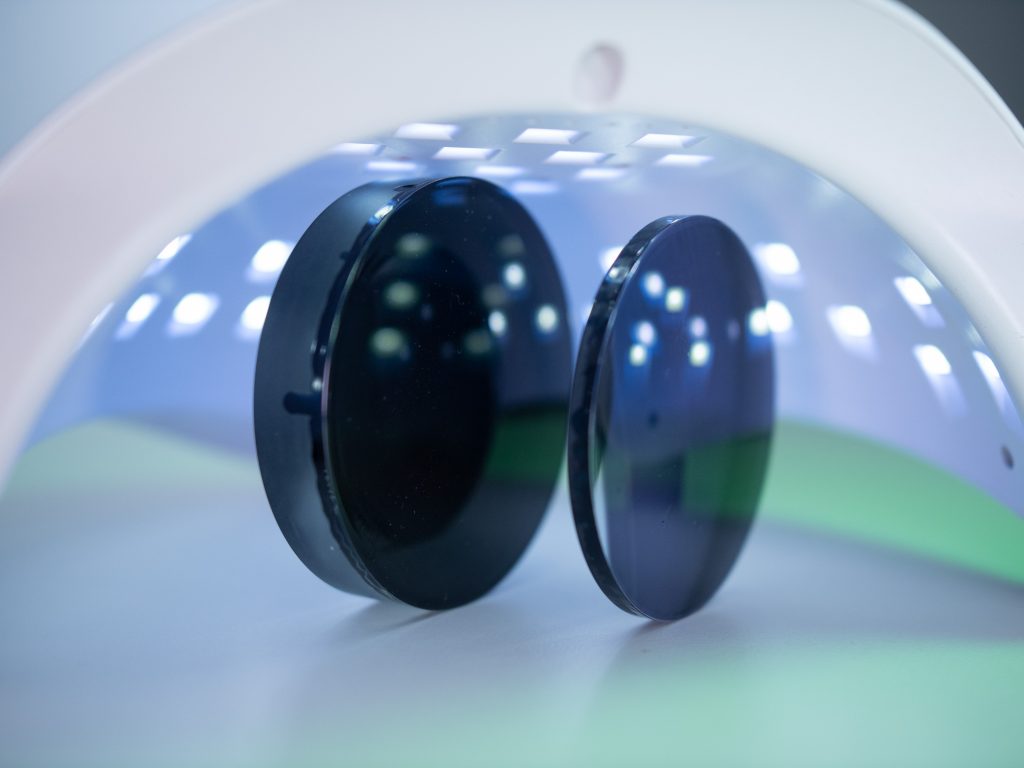

We recognized that the whole world of coatings on optical lenses – as practiced today – is predominantly a wet process. You take a lens, you dip it in a tank, you take it out, you dry it, and then you may apply a further coat. As “additive people” we call such a procedure an analog process. There is no digitization.

So we asked ourselves: “Why don’t we add the layers to the lens using a digital approach, making it more efficient, cost effective and better?”

I guess ophthalmic optics offers a great opportunity. It is a big, lucrative market that is, let’s say, hungry for innovation in many ways. There are two important aspects: labor and the environment. The way things are done today requires a lot of labor, but people often want to move onward and upward, and do things that are more challenging.

Thinking about the aspect of sustainability: In today’s lab tinting world, you have these tanks and the environment is less friendly and in some cases toxic – you can really smell that in a lab.

And that is how the idea came about to set up this company flō. Today, we are an additive manufacturing technology solution provider, specializing in digitally coating spectacle lenses of various base materials and various indexes.

What exactly do you mean when you call it a digital process? Can you explain the technology in a few sentences?

You must think of pixels. Even our computer screen is pixilated. Today, any piece of paper that you have in front of you that is printed, is pixilated. We are basically taking the surface of the lens and pixilating it. We decide exactly what drop to place where, and how to blend those drops to create a color scheme.

With the current approach, you take the lens, you dip it, take it out and it is what it is. If the tank filling is red, the lenses will be red.

With digitalization, you can control the process down to the last pixel, thus opening up a whole new realm of possibilities. The philosophy behind it is this: the more you control something, the more opportunities you have of exploiting new possibilities. The colors are the colors that you expected because it is all digitally coded, so quality is consistent.

In our world the level of control is a pixel, which is roughly an order of magnitude greater than with current processes. You are sort of zooming in on the tiny area that we call the pixel.

In a nutshell: We are able to position drops accurately on a flat or curved surface – and it is very complicated to print on curves! Secondly, we build up multiple layers, so we can take account of different substrates and stack the layers to generate improved functionality. Thirdly, we can even print structures ‒ that is cutting edge in the world of printing.

Why should labs change to an additive process?

It opens up a lot of possibilities. For instance, in color tint you can do any gradient you want, any color you want, basically anything you want. You can include graphics, you can have your logo on the side. You want a gradient of five different colors? No problem! So a new world of opportunities – personalization, customization, infinite colors – now all become achievable.

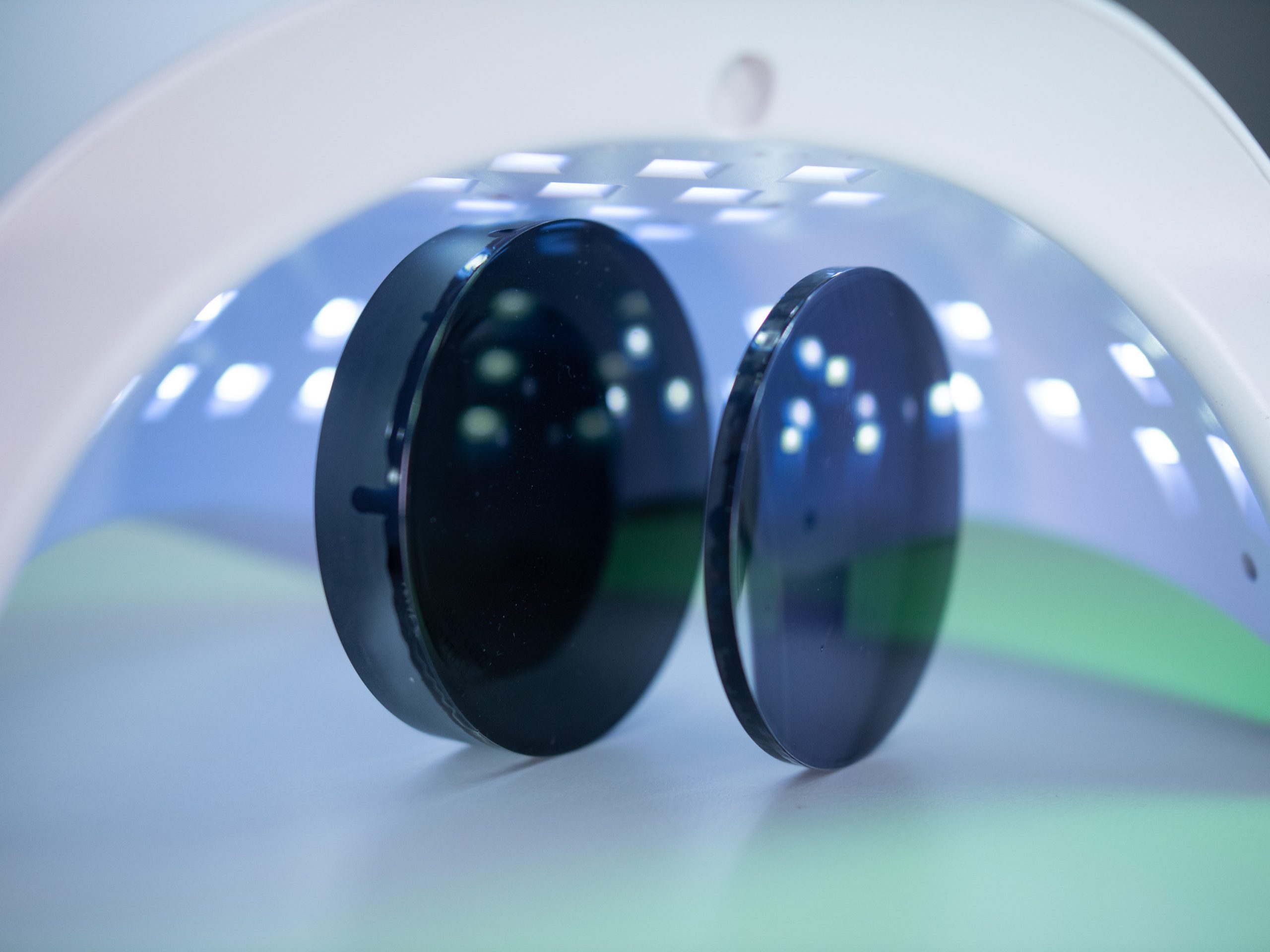

A good example is photochromic: the way this is currently done is very limited. By contrast, we can position the photochromic dyes at the optimal distances one from the other: on the XY plane in 2D, but also on the Z plane. We have multiple layers, and we can position the dyes as we wish to create optimal performance outcomes.

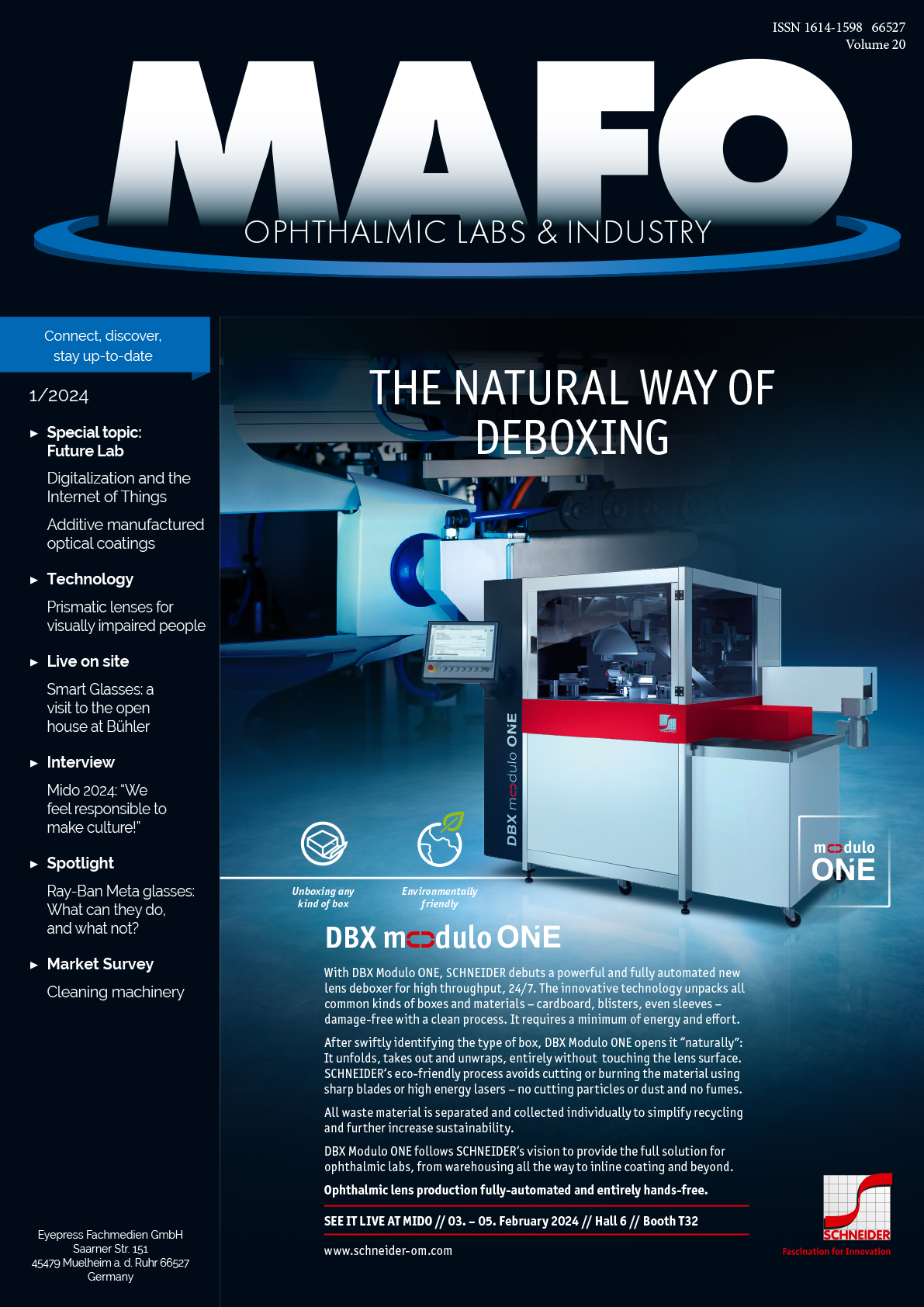

You presented your technology for the first time at Vision Expo West in Las Vegas in September 2023. Especially the photochromic coating caught attention …

Yes, Vision Expo West was amazing because we exhibited a machine which was actually printing. People could see the outcomes. We literally put in a blank lens, and three minutes later the lens we took out was fully coated.

In Las Vegas, we showcased a comparison of the industry standard photochromic compared with our own. Ours takes about a third of the time compared to the traditional one, to transition from dark to 80% transparent. It takes around 80 seconds. We can do that because we are fully in control, down to the pixel level. It is also important on what substrate and material the special dyes are applied.

The process also reduces costs, as currently labs need to hold inventory because photochromic lens coatings are not done at the lab level. The blanks still get shipped but we offer the solution at the lab level.

How good is the durability?

The mechanical properties have to be in line with industry standards. Otherwise, we would have no justificationS to exist. We are still at the development stage but we will be releasing our first products in 2024 and we already meet almost all the mechanical property requirements. Tests are being carried out with the leading labs in the world as well as the COLT Test Center to validate this. But it is also true that we still have potential to further improve our properties.

We are convinced that we can satisfy the standards that currently exist in the industry, and of course we will not release products until we meet all standards – whether with regard to durability, mechanical properties or others.

And Las Vegas also showed that we are in a very good position. We already have three customers that have opted to acquire our technology and want to be first adopters, all of them are in the US but we would love to have one in Europe, too.

You talked about photochromic coatings, and hard coating is also possible, but what other coatings can be applied ‒- AR for example?

Our vision is to have one holistic platform for all coatings. The way we see it: the labs will operate these platforms and they will be able to do all the various coatings required, but this could still take time.

We think, we are coming to market already with some very important coatings and, as time goes by, we will develop more and more of these coatings. Of course, AR is also on the radar as an additional coating, but that is more for the longer term.

What are your current challenges?

The main challenge that I foresee is introducing a new technology to the market. Change management is complicated. I was in 3D printing for almost 15 years and, when we came to customers, there was always this resistance to change, even though it ultimately brings further added-value. But the main challenge is the very conventional market, because the ophthalmic industry is a traditional industry.

Is the platform’s target group only ophthalmic labs, or could the technology also be used, for example, by opticians?

Our target audience are optical labs with industrial machines. They have a certain throughput and are part of an integrated cycle. We know the various elements of this process and we will tune in our platform, because we do not want to create a bottleneck with these machines. We will offer a throughput of 80 lenses per hour. Smaller labs or mini labs could also be the target audience, but not opticians.

At the beginning of 2023, Meta acquired the 3D printing company Luxexcel, which produces spectacle lenses using a 3D printing process. Would it be conceivable or useful to combine such additive manufacturing processes – printing the spectacle lens itself and then the coating?

I personally know Luxexcel and their CEO very well. I think it is especially interesting, that an additive company in ophthalmic optics was sold to Meta. This is further evidence that there is a need out there for additive manufacturing in ophthalmic optics.

But is there room to potentially do everything? What we are doing now is imitating existing coating solutions: photochromic tinting and hard coating. But what we aim to do in the future is to invent things that have never been done before and have never been possible before. So, I will leave that open for your audience to judge.

But coming back to Luxexcel, there are also certain things which need to be worked on in terms of speed and so on. It still takes too long to print a lens.

What is your vision for the next ten years?

In my opinion, it is really important for the audience to understand who we are. At the 3D printing company Stratasys, it took almost 20 years of investment and commitment to build a company with significant impact to be able to disrupt a given industry. But we wanted to bring added-value to customers; and we want to do that again here with flō.

We have a very committed and farsighted team. Today we have over 35 members of staff. We are still a small team but continue to grow. We aim to bring our first products to market in 2024.

Thank you for the interview