IOT: “Personalization is still not well understood”

20 years of IOT: how scientists paved the way to design freedom for every lab

Freeform for every lab: Twenty years ago, three Spanish scientists had a revolutionary idea. The innovative freeform technology should not be reserved exclusively for large groups. Instead, new software should enable every independent lab to manufacture freeform progressive lenses. The widespread personalization of ophthalmic lenses began. Today, it is 2025, and the topic is at least as relevant as it was back then. On the one hand, this is due to new developments, such as lens designs for myopia management, but also because, in the eyes of the IOT founders, the topic of personalization has not been fully understood by many people to this day.

In the northeast of the Spanish capital Madrid stands a large, modern building with open glass fronts. The logo board alone indicates that this is a hub for innovative companies – and this impression is quickly confirmed. The foosball table, sun terrace, and modern furnishings are clearly designed to attract start-ups and other original companies.

IOT moved into the new building just a few weeks ago. Around a third of the workforce is already conducting research and development at the hub, with the rest of the employees set to follow soon. The company has a total of around 100 employees, 75 of whom work at the Madrid sites. The founders are particularly proud of the research and development department, which accounts for around 40% of the workforce.

MAFO is on site to mark the company’s 20th anniversary with two of the three original founders. One is the President and CEO Dr. Daniel Crespo, the other is Chief Innovation Officer Dr. José Alonso. They take the opportunity to give us a personal tour of the company before we sit down for an interview. The third founder, Dr. Juan Antonio Quiroga, is retired already.

MAFO: How did IOT get started 20 years ago?

Crespo: All three of us are physicists, and we come from the Applied Optics research group within the physics school of the university. José was my professor. When we started the company, we wanted to walk away a little from just being in the academic realm – writing papers and so on. Instead, we wanted to have contact with real people and real problems to do useful things. We wanted to have an adventure in the real world.

MAFO: What did that adventure look like?

Crespo: The first technology we started working on was freeform lens design software. Jose had a lot of experience in ophthalmic optics, but this was not true for the rest of us. We came more from the lens metrology side and the optical science. But José told us there was this new technology called freeform and this way of making lenses. He saw an opportunity there for an independent company making lens designs for independent manufacturers.

MAFO: So, at this time only huge companies were able to produce freeform lenses?

Crespo: Yes – and that is true also before the freeform era began. Only the very big companies could create progressive lenses, because the added value was in the blank. At that time only few large companies knew how to develop a new progressive design and had the investment necessary to create all these collections of blanks. And as freeform lenses became kind of a software, it doesn’t make sense in our opinion that the same big companies that controlled the industry at that time should continue to do so via the software.

Alonso: And those large companies had a long history of making progressive lenses, but not with the flexibility that freeform gives you. They were designing lenses based on the idea that you have a fixed surface and that you put the prescription on the back. Having the flexibility of carving any progressive surface or others on the back side was something pretty new.

In contrast, the software we designed dealt from the very beginning with this flexibility. Other software from other companies at that time was always limited.

MAFO: Meaning you started out as a software company. How does that affect your company culture?

Crespo: In the beginning we were thinking as a software company. We had this whole background on ray tracing software and optimization, and we had a very clear idea that lenses had to be optimized in every direction of sight in the whole field of view.

At the same time, we had to be very humble because we didn’t know anything about labs and manufacturing. The only chance we had of success was listening to our customers, as they are the ones that know how to make lenses.

Those are the two pillars of IOT. On the one hand, we are scientists wanting to innovate and have fun by learning and creating new things. And on the other hand, we focus on a very strong customer orientation. Even today we are still scientists at heart – more than entrepreneurs or businesspeople.

MAFO: What exactly are the steps involved in creating a new lens design?

Alonso: In many cases everything starts with an idea from the optical design group or from the clinical trial group when they recognize a market gap or specific need. Then we make the designs based on our data, and we produce a prototype.

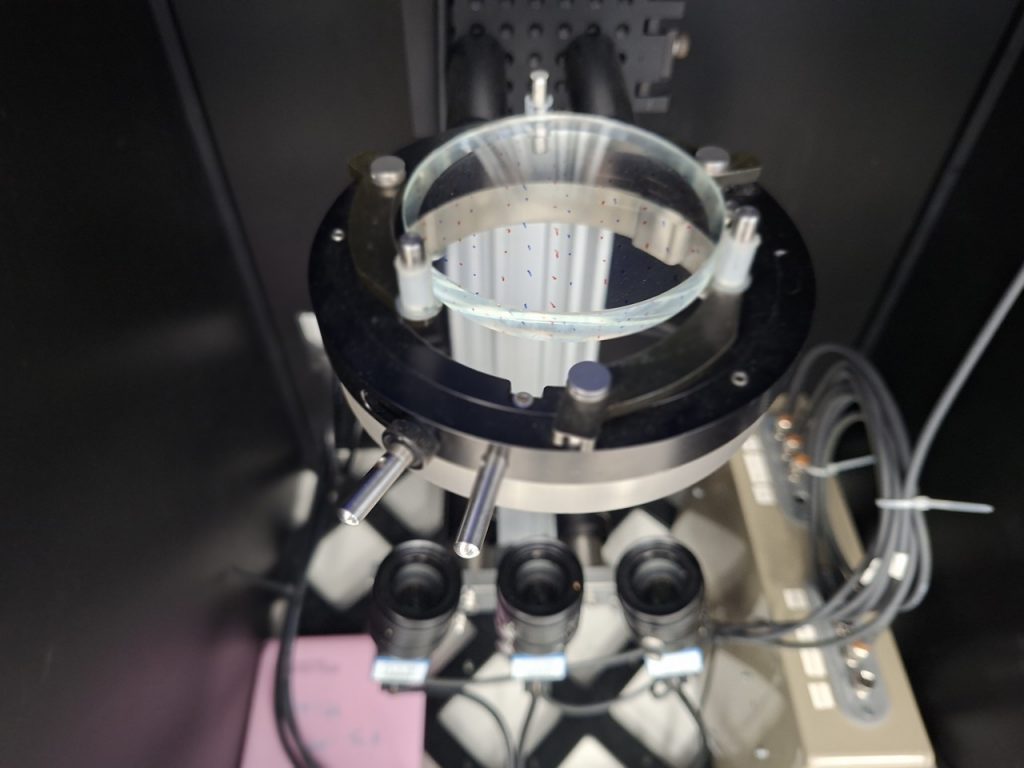

In the next step, we conduct a clinical trial comparing the lens with another lens. We’re typically conducting 15 clinical trials a year; that is more than one per month. We are also very involved in using eye tracking, for example, to gather information about visual behavior.

Finally, we extract results and decide whether the idea is good or not. If it is good, it will go for a product. If not, the cycle will begin. Our design software is our main business line by far – it´s like 80% of our business.

MAFO: What are the other 20%?

Crespo: The other 20% is photochromic lenses. That links to the next chapter in our history. In 2010, Younger Optics became the majority owner of IOT as we needed a bigger partner and investor to help the company grow. Younger Optics is also a private company that’s owned by David Rips and Tom Balch. We understood each other very well and had similar values. They helped us to open many doors, and in 2010, we started growing very fast in the United States and Europe.

MAFO: What is currently the most innovative product in your portfolio and why?

Crespo: Choosing the best progressive for every individual person might be a key challenge today, as there are so many aspects. Some are related to your prescription, some to your history or other aspects like the frame chosen, lifestyle, and special interests.

Therefore, we now include AI in designing the lens. We are trying to gather all the data we can from the patient, including lifestyle, previously worn lenses, and more, trying to create the most satisfying lens. We keep training the systems with feedback from users, and that’s called Endless AI.

The project is also evolving into a lens recommendation system for opticians. As they choose a combination from hundreds of options. Those decisions are sometimes made randomly, or they are based on preconceptions. Our system helps opticians to advise more systematically in any part of the world, as opticians are trained differently all over the globe.

MAFO: Critics sometimes say that progressive lenses have already reached the end of their development. How do you respond to such statements?

Crespo: You can see in real life that there’s still a lot of work to do. I’m 51, and all my friends are starting to need progressives now – but half of them hate it. They went to an optician’s store, and they made lenses for them, but they are not satisfied at all. But when I say, come here and let’s measure you, then you see, if you make a good measurement and you choose carefully, you can get many more people happy with their lenses.

I think what the industry needs to do instead of all this marketing hype is that we need to solve the problem of personalized eye care. This requires a lot of data integration.

In the store, the optician knows so many things about the patient. They know how many lenses they’ve been wearing or how their prescription has been evolving. But then the lab makes the lens, and they don’t know anything about this background. They only have a small data standard file.

What we want is to make these two systems talk to each other. When I’m making the lens, I want to know everything there is to know about the patient. Because then I can make the best possible lens. You can make a difference like that, but companies need to care enough.

Because many people walk outside an optician’s store, but they will never know that they could have seen better with other lenses. But we know that because we’re doing trials here. It makes a difference!

Alonso: And when people say there is no more room for improvement because we’ve reached the top – this might be true from a statistical point of view, but not individually. I’ll tell you an example. You may start a clinical trial with the best lens from manufacturer X, and then you will see that statistically it is 0.5% better. But then you go person by person by person, and you will see that for some people the design is 60% worse than the previous one. Individually there can be huge differences – also you cannot see it in the general statistic. Personalization is still not well understood.

Crespo: I think there are two tendencies in the industry. One of them wants to just simplify things – the big retailers and online shops. They want to know what the best lens is to put on everybody. We believe in another approach, which is personalized lenses are healthcare. And these improvements don’t always come from the math but from how we all work together.

MAFO: How important do you consider lenses for myopia management in children?

Alonso: Nowadays there is a pretty consistent body of research describing the risk of myopia development considering genetics, lifestyle, age, and the refractive history of the kid. And there are a lot of scientists and experts who are considering the data is well founded and the lenses to work well, so we should trust those models. Meaning there is no disadvantage for kids when wearing those lenses.

But this is not saying that every myopic kid should have a myopia control lens. You still have to evaluate the risk. There are tools for doing that, and depending on the results, you may prescribe one of these lenses.

We currently have a product that has been tested in a three-year clinical trial with children and has demonstrated good performance with Caucasian kids. And right now, we are working with a new design, but we still have discrete elements on the back side to control myopia.

MAFO: In your opinion, which technological trends in ophthalmic optics are currently the most exciting?

Crespo: I think augmented reality, like lenses that incorporate displays, and similar things are very exciting. There seems to be a big push to move things in that direction, and they need to find solutions on how to serve people with prescriptions. We hope we can have something to contribute there.

MAFO: Where do you see IOT in ten years or so when thinking about products, markets, and corporations?

Crespo: In ten years, we would like that most lenses in the world will be made using IOT technology one way or another. We really would like to be even more relevant in the future and do more exciting things in this industry.

What’s unique about IOT is that we are a team of about 100 people, and if you were to gather them in one room, you’d have know-how about everything: the math, the optics, the software, the manufacturing and the chemistry. Of course, large companies in this industry have this know-how too, but they have it distributed across teams of thousands of people.

So, I think we are in a very unique position to develop unique technologies for this industry because of the amount of talent, the scope of the skills and the way we’ve built the company is very unique.

MAFO: Thank you very much for the interview.