Historical grinding machine for spectacle lenses

Mineral glass is difficult to work, especially the rock crystal beryl initially used to make spectacle lenses, because of its hardness. So anyone who wanted to turn a piece of glass into a visually effective lens needed a lot of patience and perseverance. Whether a lens could ultimately deliver a distortion-free image depended entirely on the precision with which it was worked. Thus it is not surprising that, in the late Middle Ages, methods were sought based on wind and water power to produce spectacle lenses with the required finish, if possible without the need for human labor. The advent of the industrial revolution two centuries ago with its motor-driven machines finally made it possible to manufacture spectacle lenses on a routine basis.

By Dr. Hans-Walter Roth

In the beginning grinding of spectacle lenses was done entirely by hand. Thus chroniclers report dozens of unqualified workers spending days giving the blanks supplied by the glassworks their desired shape. On grinding machines, whose antecedent was the potter’s wheel, one side of the lens was ground to a shape corresponding to a spherical surface. The other side was initially flat, as with lenses for reading placed on the page. Only later did lenses become biconvex. Provided the diameter and refractive index of the material were known, the strength of the spectacle lens could be calculated from the difference between the central thickness and the edge thickness. Prior to the introduction of the metric system two centuries ago when the diopter was introduced as a measure of spectacle lens strength, previously only the focal length was specified. It was easy to determine: you just had to hold the lens up to the sun and, by focusing the rays of light for example on a piece of paper, you could find the focal point. The oldest surviving pair of glasses was found in 1953 under the choir stalls in the nunnery at Wienhausen, founded in the 13th century. Like most glasses at that time, the strength of the lenses was +3.4 diopters, showing that they served as a reading aid to compensate for presbyopia.

The beginnings of automation

With the invention of printing, the demand for reading glasses increased dramatically as more and more people learnt to read. The lengthy process of grinding by hand, however, prevented mass production of reading aids. Thus it became imperative to automate the lens-grinding process. As early as the 16th century, there had already been some quirky constructions to grind several lenses in series simultaneously.

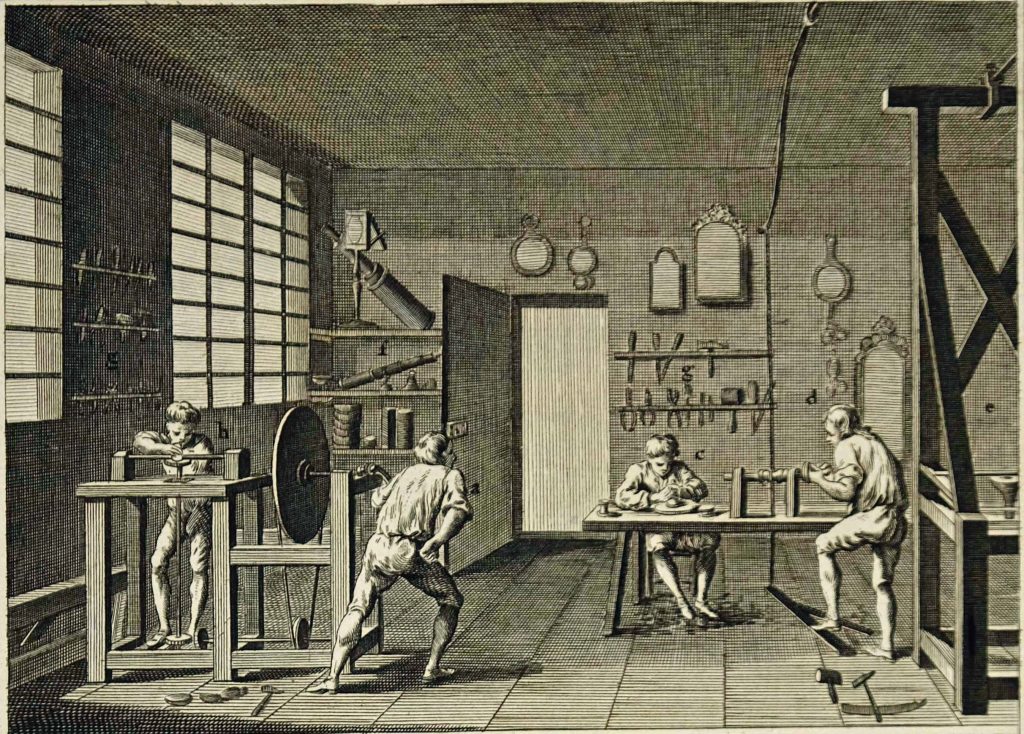

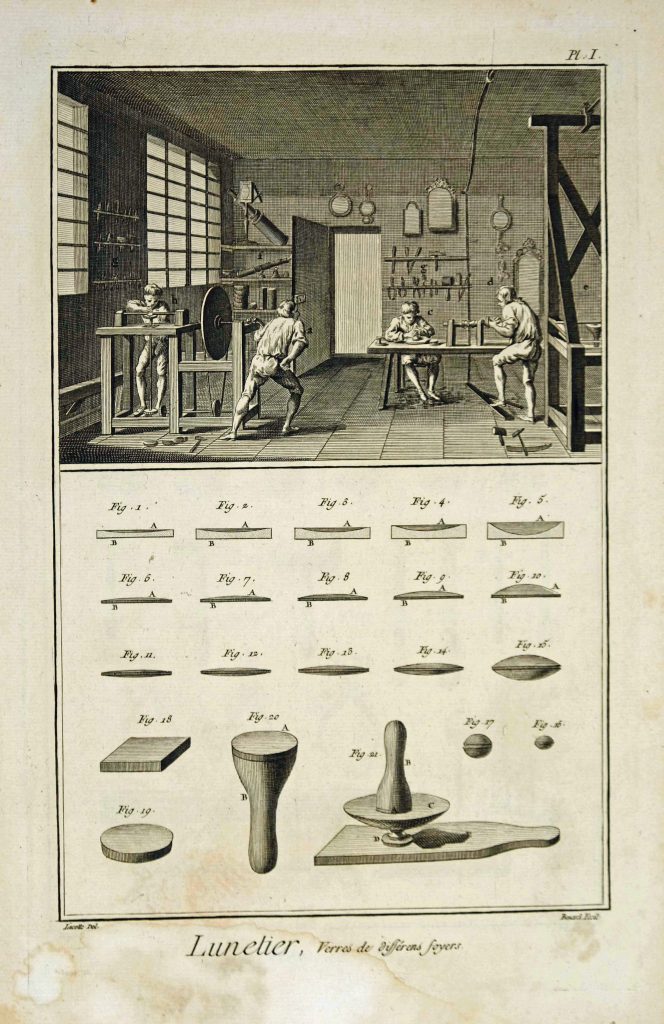

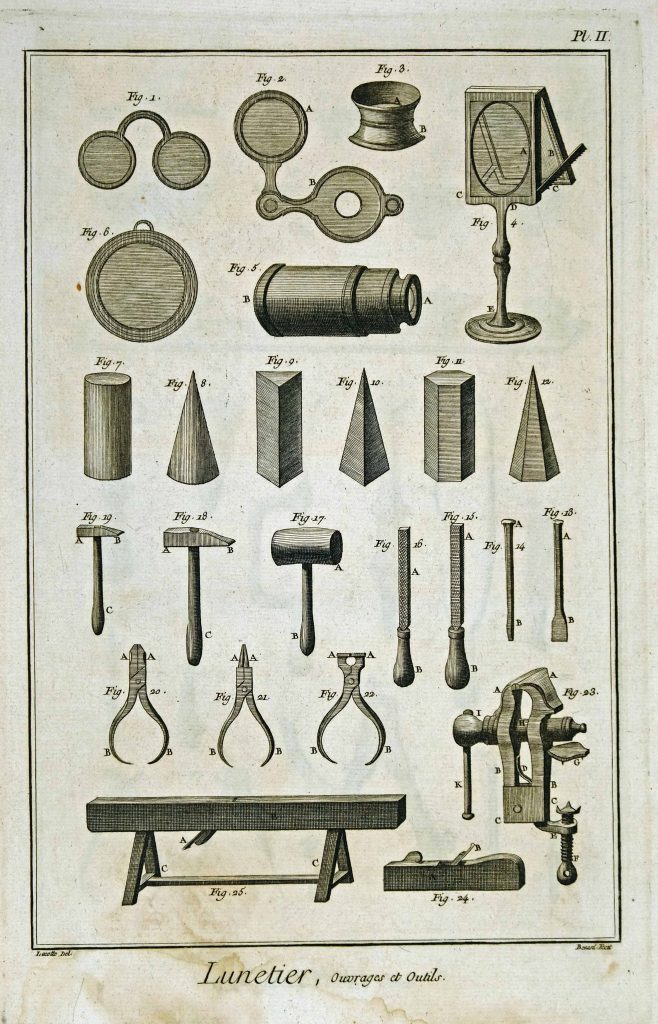

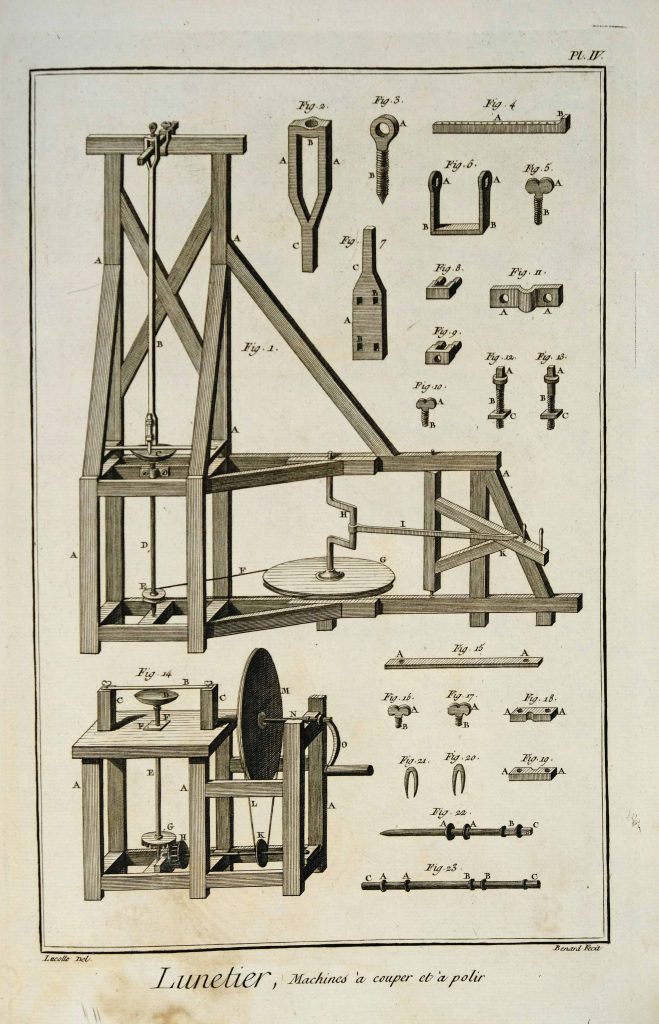

Diderot’s encyclopedia, published in France from 1751, includes illustrations of various devices and tools used to make lenses for a variety of optical instruments, including spectacles. The grinding machine has a solid wooden frame similar in principle to that of a potter’s wheel. A large flywheel is driven by a hand-operated crank, with a leather drive belt transmitting the rotation to a small wheel, thus multiplying the speed of rotation by a factor of 1: 5. The precast biconvex glass lens is mounted in a concave support cup on a vertically mounted rotating rod. This in turn is connected via a wooden bevel gear to the small wheel in such a way that one turn of the hand crank makes the lens rotate five times about its own axis.

Above the lens holder there is a metal bar fixed with two wing nuts, to which various grinding and polishing heads can be attached. These are shown in the subsequent figures with different radii of curvature, showing that different lens thicknesses can be ground on the same machine. The concave polishing heads and the holders for the lenses are made of metal – usually brass – prefabricated on a lathe. A thin piece of leather between the lens and the holder prevents the surface of the lens from being scratched while it is being worked and held securely.

The illustrations shown here are from one of the numerous editions of the Diderot encyclopedia. They were purchased individually from one of the many booksellers on the banks of the Seine in Paris. Unfortunately, today there are hardly any complete editions of the famous encyclopedia from the 18th century on the market; savvy dealers preferring rather to separate them and sell the pages individually, in order to make more money.

All pictures in this article are courtesy of the Institute for Scientific Contact Optics Ulm.