The myth of night myopia – current research clarifies

An interview with Dr. Philipp Hessler

For a long time, night myopia was considered the main cause of poor vision at dusk and at night. However, the studies on which this assumption is based are highly fragile. Current research findings reveal surprising insights into what actually happens physiologically in the eye when it gets dark – and, above all, what does not happen.

The most extensive research activity in the field of vision in darkness took place between the 1950s and the 1980s. The studies on this topic are therefore quite old, and the measurement technology used in the investigations at that time is now long outdated. In contrast, there have been only a few publications on night vision in the last 40 years.

One person who has taken up this neglected topic is Dr. Philipp Hessler. Hessler already dealt with vision in darkness in his 2021 dissertation. He continued his research and has since been regularly explaining the topic in specialist lectures and publications. The expert has already found surprising answers to many questions, but also exciting new questions that would be worth further research to answer.

MAFO: What are the causes of poor vision at dusk and at night according to specialist literature?

Hessler: The literature postulates a refractive change in darkness, also known as night myopia. This has long been attributed to three factors.

The first is the onset of the resting state of accommodation in visual situations without any fixation or accommodation stimuli. However, this assumption is based on complete darkness! According to the literature, this accounts for 2-3 diopters.

The second factor is spherical aberration, which can often be measured when the pupil dilates. With positive spherical aberration, the peripheral rays are refracted more strongly than the central rays. When the pupil dilates, these peripheral rays have a correspondingly stronger effect, resulting in myopia.

The third factor is the so-called Purkinje shift, i.e., the shift in maximum spectral light sensitivity, which is around 555 nanometers during the day. At night, this shifts to around 505 nanometers. This shift in light sensitivity towards blue causes relative myopia of between 0.2 and 0.5 diopters, depending on the study. This can be explained by chromatic aberration.

It has therefore long been assumed that these three aspects – the resting position of accommodation, spherical aberration, and Purkinje shift – are responsible for the development of night myopia.

MAFO: Do your study results confirm the theory that night myopia is the main reason for poor vision in the dark?

Hessler: The results do not confirm this; rather, these are likely to be isolated cases. In our study, approximately 10 to 15% of participants were affected by night myopia – or rather twilight myopia – of -0.25 to -0.5 diopters. All others showed no change in refraction.

However, due to the small sample size, little can be said about the prevalence in the general population, as this was not an epidemiological study. But today we know that night myopia plays hardly any role in everyday life, with the exception of individual cases.

MAFO: You also differentiate between twilight and night myopia. Why is this distinction so important?

Hessler: That’s an important point. Night myopia in the true sense of the word assumes scotopic conditions, i.e., complete darkness. In this case, we would have no fixation stimuli, no accommodation stimuli, and no colors. However, we never actually encounter such conditions in everyday life, except perhaps when we get up at night in a pitch-dark room to go to the bathroom.

In contrast, we have lights everywhere in traffic, whether they be streetlights or car headlights. Even the interior lighting in our own cars ensures that we have mesopic conditions rather than scotopic ones.

And we have color stimuli when driving. We see traffic light colors, street signs, car traffic signs, and much more. This situation differs significantly from seeing in complete darkness without any fixation or accommodation stimuli. If we now consider the factors mentioned above, such as the resting position of accommodation, it is quite logical that twilight myopia is significantly weaker and that night myopia in complete darkness is irrelevant for everyday life.

MAFO: What factors are instead responsible for poorer vision at dusk and at night?

Hessler: First, we should consider the most obvious factors. The first point should be to take a close look at your glasses. Is the correction status of the glasses correct? The second point sounds even more obvious, but how many people have their glasses or car windows perfectly clean? And the third common factor: Are the lenses scratched? Such things have a major influence.

Another major factor influencing poor vision at dusk and at night is physiological visual acuity reduction, i.e., visual acuity decreases as luminance decreases. For every tenfold decrease in luminance, visual acuity deteriorates by one to two levels. In a dark room, it is therefore to be expected that visual acuity will “only” measure 0.6 or 0.8. Some people are less bothered by this than others, as people have different levels of sensitivity when it comes to vision.

Another cause can be the eye itself – everything in the eye, from the tear film to the retina, can be structurally affected. A poor tear film significantly affects visual acuity and contrast. A simple tip here would be to use eye drops before driving at night.

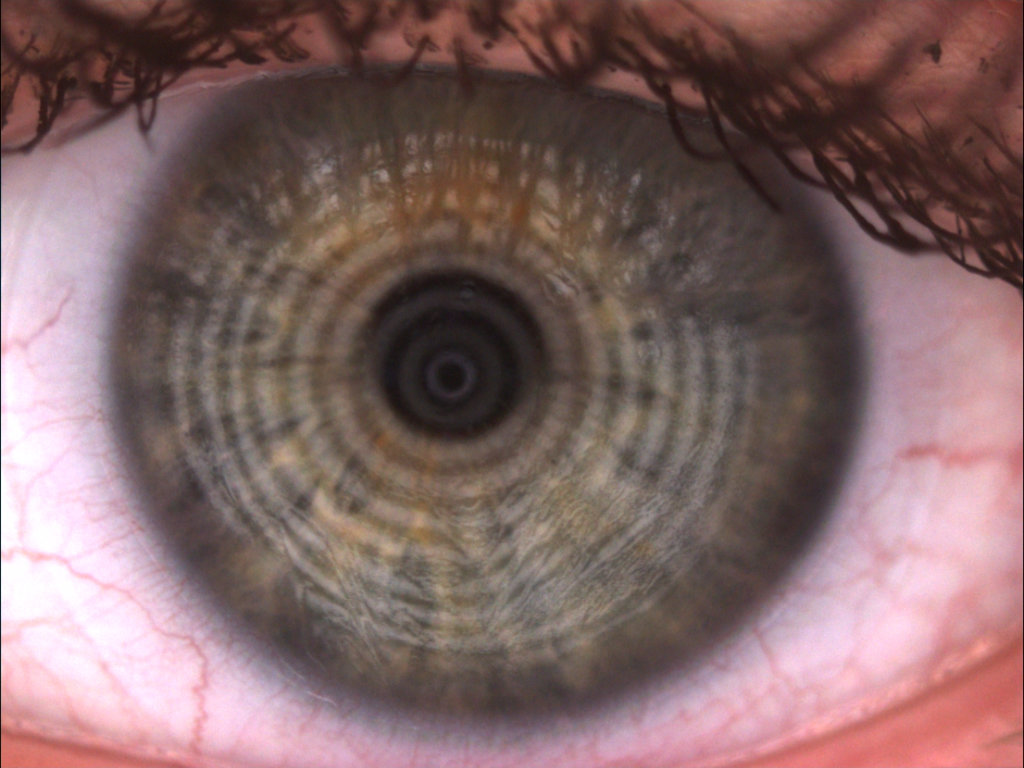

But in principle, any structure in the eye can impair vision in twilight. Corneal irregularities can greatly affect vision, especially when the pupil becomes large. Lens opacity can make a big difference, but so can pupil movement, a cloudy vitreous body, and even retinal pathologies. It is also worth asking how often the person drives at night, because if someone only drives at night once every two weeks, they will feel less confident than a professional driver who drives in the dark almost every day.

MAFO: Does age also affect vision at dusk and at night?

Hessler: With increasing age, we find the above-mentioned causes such as dry eyes or media opacities more frequently. In addition, contrast sensitivity is usually reduced, and the entire adaptation process can be slower.

MAFO: What is a sensible examination procedure for clearly evaluating the reasons for poorer vision at dusk and at night?

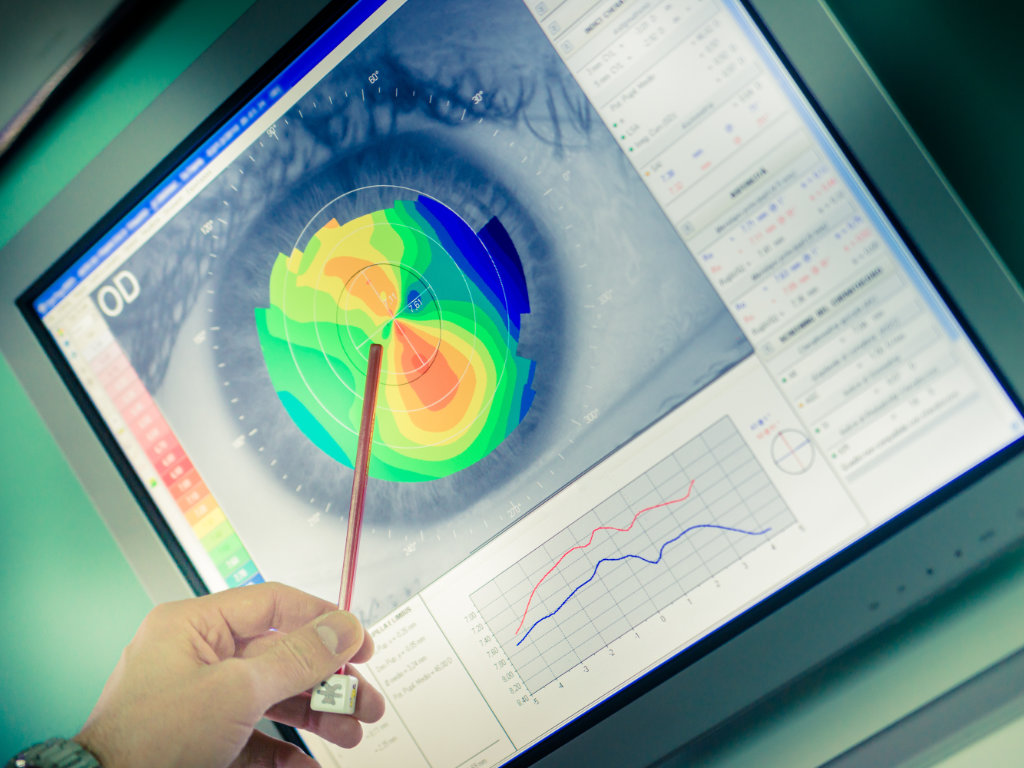

Hessler: You have to look for the cause. We start with tear film analysis, which is crucial for nighttime driving. Then, with aberrometry, we have an objective way of checking refractions at different pupil diameters and also measuring higher-order errors. Slit lamp examination is essential for examining the anterior segment of the eye and the transparency of the media. Corneal topography reveals irregularities, and finally, retinal examination would also be useful to detect retinal abnormalities.

Then we have the test for night myopia itself. We should check for this despite the study findings, as there are individual cases that are affected by it. A normal refraction test should be performed under mesopic conditions, i.e., the room is completely darkened. It is best to use a vision test chart, and it is important not to use a display that may be so bright that it creates photopic conditions.

Now, in the winter months, you can also go outside, find a fixation object, and perform a reality vision test in nature.

MAFO: Are there any new technologies or materials that could improve vision in low light conditions? For example, special lenses with a yellow tint or similar?

Hessler: Personally, I am not aware of any published studies that provide clinical evidence that these methods bring about an objective or at least subjective improvement. I would therefore advise against offering such things across the board, as there are often other causes responsible for poorer vision. On the other hand, I have seen individual cases where special filters or yellow tints help wonderfully, so I would by no means condemn them. If you want to offer filters or special anti-reflective coatings, I recommend going outside with customers in the dark, holding up the filters or similar products, and asking whether they actually see an improvement.

MAFO: What was the most exciting finding for you personally in your studies on vision at dusk and at night?

Hessler: I found it very exciting that all the causes cited in the literature as reasons for poorer night vision are mainly based on assumptions rather than empirical research. And that classic factors such as those found throughout the literature, for example Purkinje shift, are irrelevant for night driving because they only occur under scotopic conditions. The same applies to the Kohlrausch kink, the kink in the dark adaptation curve that occurs during the transition from cone vision to rod vision, which is also irrelevant for night vision.

MAFO: What future research questions can be derived from the study results so far?

Hessler: A multifactorial study could be conducted, incorporating all conceivable factors, to identify the main reason why most people have poor vision at dusk and at night. This would enable us to determine whether it is truly physiological visual acuity reduction or perhaps the tear film, etc. It would also be interesting to conduct epidemiological studies to determine the percentage of the population affected.

Another very specific but also interesting question would be the significance of blue cone sensitivity on the shift in overall spectral sensitivity. Overall, there are still some unanswered questions, so further research in this area makes perfect sense.

MAFO: Thank you very much for the interview!